The student loan interest deduction, a seemingly straightforward tax break, reveals a complex landscape of limitations and eligibility requirements. Understanding these nuances is crucial for borrowers seeking to minimize their tax burden and effectively manage their student loan debt. This guide delves into the history, current limitations, and potential future of this vital deduction, providing clarity and insight for both current and prospective borrowers.

From its inception, the student loan interest deduction has aimed to ease the financial strain of higher education. However, the ever-evolving landscape of federal tax policy has introduced significant changes, including income limitations and restrictions on qualifying loans. This exploration will examine these changes, their impact on various income levels, and compare the deduction to other student loan assistance programs. Ultimately, we aim to empower you with the knowledge to navigate this system effectively.

History of the Student Loan Interest Deduction

The student loan interest deduction, a provision within the US tax code, allows taxpayers to deduct the amount they paid in student loan interest during the tax year. This deduction aims to alleviate the financial burden of student loan debt, a significant concern for many Americans. Its history reflects a shifting understanding of the role of higher education in the national economy and the evolving landscape of student financing.

The deduction’s evolution has been marked by several legislative changes, reflecting fluctuating political priorities and economic conditions. Initially, the deduction was a relatively modest provision, but its scope and impact have expanded over time, alongside the rising costs of higher education and increasing student loan debt levels.

Legislative Timeline and Evolution of the Deduction

The student loan interest deduction wasn’t always a permanent fixture of the tax code. Its journey involved several key legislative acts that shaped its parameters and accessibility.

| Year | Legislation | Significant Changes | Maximum Deduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1986 | Tax Reform Act of 1986 | Introduced the student loan interest deduction as a temporary provision. | $2,500 |

| 1997 | Taxpayer Relief Act of 1997 | Made the deduction permanent and increased the maximum deduction. | $2,500 |

| 2001 | Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 | Adjusted the deduction’s parameters in response to economic factors. | $2,500 |

| 2008 | American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 | Further modified the deduction’s provisions; this included temporary increases in the maximum amount deductible. | $2,500 (Later increased temporarily) |

| 2017 | Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 | While not eliminating the deduction, this act resulted in changes impacting eligibility. For example, the standard deduction increased, meaning that some taxpayers who previously itemized to take the deduction might no longer find it beneficial. | $2,500 |

Initial Purpose and Intended Beneficiaries

The initial purpose of the student loan interest deduction was to encourage higher education attainment by offsetting the financial burden of student loans. The intended beneficiaries were primarily students and recent graduates repaying their student loans. The deduction was seen as a way to promote economic growth by investing in human capital. This policy aligned with the idea that a more educated workforce would contribute to a stronger economy.

Current Limitations and Eligibility Requirements

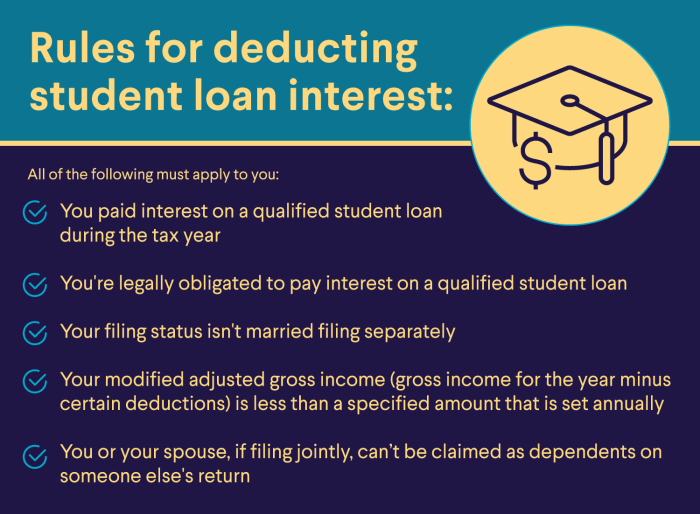

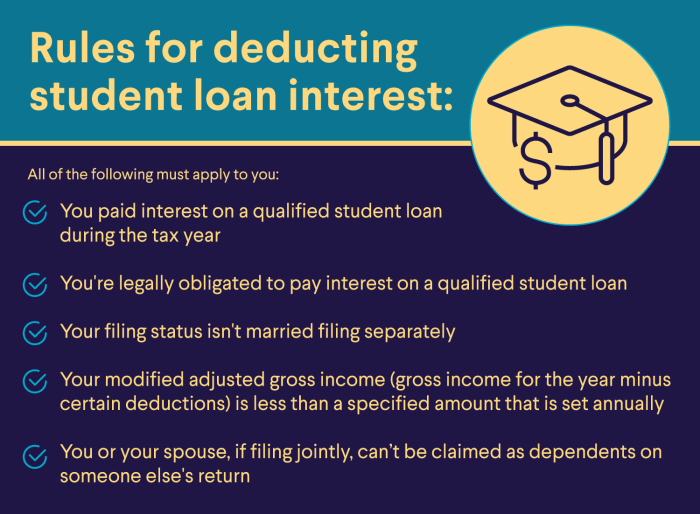

The student loan interest deduction, while beneficial, is subject to several limitations and eligibility requirements. Understanding these factors is crucial for determining whether you qualify and how much you can deduct. This section details the current rules governing this deduction, clarifying the maximum deduction, income limits, qualifying loan types, and filing status considerations.

The maximum amount of student loan interest you can deduct annually is $2,500. This is regardless of how much interest you actually paid during the year; the deduction is capped at this amount. It’s important to note that this is a deduction, meaning it reduces your taxable income, thereby lowering your overall tax bill. It does not directly refund the full amount of your student loan interest.

Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) Limitations

The amount you can deduct is also affected by your Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI). MAGI is your adjusted gross income (AGI) with certain deductions added back in. For the 2023 tax year, the student loan interest deduction is phased out for single filers with MAGI exceeding $85,000 and for married couples filing jointly with MAGI exceeding $170,000. This means that as your MAGI increases beyond these thresholds, the amount of the deduction you can claim gradually decreases until it reaches zero. For example, a single filer with a MAGI of $90,000 would likely see a reduced deduction, while a filer with a MAGI significantly above the limit would not be eligible for the deduction at all. The exact phase-out calculation is complex and best determined using tax software or consulting a tax professional.

Qualifying Student Loans

The student loan interest deduction applies only to loans taken out for educational expenses. This includes federal student loans (like Stafford, Perkins, and Grad PLUS loans), and private student loans. However, loans used for expenses other than qualified education expenses do not qualify. It’s important to maintain accurate records of the loan amounts and the interest paid specifically for educational purposes. Loans used for personal expenses or non-educational purposes are ineligible for the deduction.

Filing Status and Claiming the Deduction

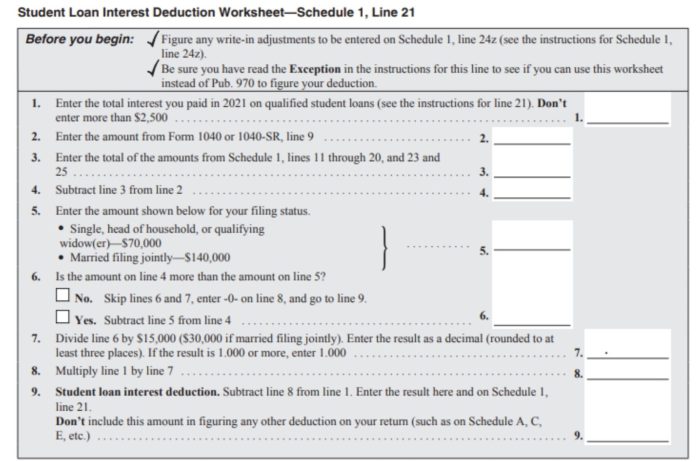

To claim the student loan interest deduction, you must file your federal income tax return as either single, head of household, married filing jointly, or qualifying surviving spouse. The deduction is claimed on Form 1040, Schedule 1 (Additional Income and Adjustments to Income). You will need Form 1098-E, Student Loan Interest Statement, from your lender, which shows the amount of interest you paid during the year. Accurate record-keeping is essential for a successful claim, as the IRS may request supporting documentation to verify the deduction. Failing to maintain accurate records can lead to delays or denial of the deduction.

Impact of the Deduction Limitation on Different Income Levels

The student loan interest deduction, while intended to alleviate the financial burden of higher education, is significantly impacted by the taxpayer’s Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI). The phase-out range, where the deduction begins to decrease and eventually disappears, creates a disparity in the benefit received by individuals across different income brackets. This section will explore how income level influences the accessibility and value of this deduction.

The MAGI threshold plays a crucial role in determining the extent to which a taxpayer can benefit from the student loan interest deduction. For single filers, the deduction begins to phase out once MAGI surpasses a certain level, and completely disappears at a higher threshold. Similarly, married couples filing jointly have a different, generally higher, set of MAGI thresholds for the phase-out. This means that individuals with higher incomes receive a smaller deduction, or none at all, while those with lower incomes may receive the full deduction.

MAGI Thresholds and Deduction Phase-Out

The interaction between MAGI and the deduction’s value can be complex. Let’s consider a simplified example. Suppose the maximum deduction is $2,500, and the phase-out begins at $70,000 MAGI for single filers, completely phasing out at $85,000. A single filer with a MAGI of $70,000 might receive a reduced deduction, perhaps $1,250. Someone with a MAGI of $85,000 would receive no deduction, while an individual with a MAGI of $60,000 would likely receive the full $2,500 deduction. The exact reduction within the phase-out range is determined by a formula specified by the IRS, resulting in a gradual decrease in the deduction as MAGI increases.

Income Disparity and Access to the Deduction

The progressive nature of the MAGI-based phase-out creates a clear disparity in access to the student loan interest deduction. Higher-income taxpayers are disproportionately affected by the limitations, potentially receiving a significantly smaller benefit or no benefit at all. This contrasts sharply with lower-income taxpayers who may fully utilize the deduction to offset their student loan interest payments. This disparity highlights a potential inequity in the system, where the intended relief is less accessible to those who may already be struggling with a larger student loan debt burden due to higher education costs.

Graphical Representation of Income and Deduction Value

A graph illustrating this relationship would show MAGI on the x-axis and the value of the student loan interest deduction on the y-axis. The graph would start at the origin (0,0). Initially, the line would be horizontal at the maximum deduction amount ($2,500 in our example) until it reaches the starting point of the phase-out range ($70,000 in our example). From there, the line would slope downwards, linearly decreasing to zero at the complete phase-out point ($85,000 in our example). This visually demonstrates how the deduction’s value diminishes as income increases, ultimately reaching zero for taxpayers exceeding the phase-out threshold. The graph would clearly show a plateau at the maximum deduction, followed by a linear decline, emphasizing the impact of income on the deduction’s benefit. For married couples filing jointly, a similar graph could be constructed, but with different phase-out thresholds reflected on the x-axis. The shape would remain essentially the same: a plateau followed by a linear decline to zero.

Comparison with Other Student Loan Assistance Programs

The student loan interest deduction, while helpful, is just one piece of the puzzle when it comes to managing student loan debt. Understanding how it compares to other federal and state programs is crucial for borrowers to make informed decisions about their financial strategies. This section will compare the student loan interest deduction with other prominent student loan assistance programs, highlighting their relative strengths and weaknesses to help you determine which might be most beneficial in your specific situation.

Several federal and state programs offer assistance beyond the interest deduction, each with its own eligibility criteria and benefits. These programs often target different aspects of student loan repayment, such as income-driven repayment plans, loan forgiveness programs, and state-specific grants or tax credits. A comprehensive comparison allows borrowers to leverage the most suitable options for their financial circumstances.

Comparison of Student Loan Assistance Programs

The following table compares the student loan interest deduction with other prominent federal and state programs. Note that program specifics, including eligibility criteria and benefit amounts, can change, so it’s crucial to consult the official program websites for the most up-to-date information.

| Program | Type | Key Features | Benefits | Drawbacks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Student Loan Interest Deduction | Federal Tax Deduction | Deduction for interest paid on eligible student loans; income limitations apply. | Reduces taxable income, lowering overall tax liability. | Limited deduction amount; income restrictions may exclude some borrowers; only benefits those who itemize. |

| Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans (e.g., ICR, PAYE, REPAYE) | Federal Repayment Plan | Monthly payments based on income and family size; potential for loan forgiveness after 20-25 years. | Lower monthly payments, making repayment more manageable; possibility of loan forgiveness. | Longer repayment periods; forgiven amount is considered taxable income in some cases. |

| Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) | Federal Loan Forgiveness Program | Forgives remaining federal student loan debt after 120 qualifying monthly payments under an IDR plan while working full-time for a qualifying employer. | Complete loan forgiveness after meeting stringent requirements. | Strict eligibility requirements; lengthy repayment period; program changes can impact eligibility. |

| State-Specific Student Loan Assistance Programs | State Programs | Vary widely by state; may include grants, tax credits, or repayment assistance programs. (Examples: Some states offer tax credits for student loan interest payments, while others may have programs specifically designed to assist borrowers in certain professions.) | Potential for additional financial assistance beyond federal programs. | Eligibility criteria and benefits vary significantly by state; may not be available in all states. |

Situations Where One Program Might Be More Advantageous

The optimal choice of student loan assistance program depends heavily on individual circumstances. For example, a high-income borrower might find the student loan interest deduction less beneficial due to income limitations, while an individual working in public service might find PSLF more advantageous than the interest deduction. Similarly, borrowers with low incomes might benefit most from IDR plans, while those in states with robust state-level programs could find additional support there. Careful consideration of individual income, employment, and loan amount is crucial in determining which program or combination of programs offers the greatest advantage.

Potential Reforms and Policy Considerations

The student loan interest deduction, while intended to ease the burden of student debt, has faced criticism regarding its effectiveness and equity. Reforms are necessary to ensure the deduction remains a relevant and impactful tool within a broader strategy for addressing student loan debt. Several potential avenues for reform and alternative approaches warrant consideration.

Alternative Approaches to Student Loan Debt Relief

Several alternative approaches to student loan debt relief could be more effective and equitable than solely relying on the interest deduction. These alternatives often aim to address the root causes of student debt, such as rising tuition costs and limited access to affordable higher education. A comprehensive strategy might involve a combination of these approaches.

Income-Based Repayment Reforms

Reforming income-based repayment (IBR) plans could significantly impact borrowers. Current IBR plans often leave borrowers with substantial debt even after decades of payments. Strengthening IBR by lowering the percentage of discretionary income allocated to repayment or shortening the repayment period could provide more substantial relief. For example, a shift from 10% to 5% of discretionary income could drastically reduce monthly payments for many borrowers, leading to faster debt reduction. This reform would likely increase the federal government’s outlay but could also stimulate economic activity by freeing up borrowers’ disposable income.

Targeted Debt Forgiveness Programs

Targeted debt forgiveness programs, focusing on specific demographics or fields of study, offer another approach. For instance, forgiving debt for borrowers in public service or those pursuing careers in high-need fields like healthcare or education could incentivize individuals to enter these professions while addressing societal needs. This approach requires careful consideration of eligibility criteria to avoid unintended consequences and ensure equitable distribution of resources. A similar program in the past saw the forgiveness of loans for teachers, and its success could inform future designs.

Tuition Reform and Increased Funding for Higher Education

Addressing the root causes of student debt is crucial. Subsidizing tuition costs, increasing funding for public colleges and universities, and promoting more affordable alternatives like community colleges would reduce the need for substantial borrowing in the first place. This long-term approach would require significant investment but could yield substantial long-term benefits in terms of reduced debt burdens and increased access to higher education. The success of this approach depends heavily on political will and a commitment to sustainable funding mechanisms.

Arguments for and Against Expanding or Modifying the Deduction

Arguments for expanding the deduction often center on its potential to stimulate the economy by increasing disposable income for borrowers. Proponents argue it provides targeted relief to those most in need and encourages investment in education. However, opponents point to its regressive nature, as higher-income borrowers benefit disproportionately. Concerns also exist about its cost-effectiveness compared to other approaches, and its potential to exacerbate existing inequalities in access to higher education. Modifying the deduction to target lower-income borrowers or tying it to specific needs-based criteria could improve its equity and effectiveness.

Economic and Social Impacts of Different Policy Options

The economic and social impacts of different policy options are multifaceted and complex. Income-based repayment reforms, for example, could lead to increased consumer spending and economic growth, but also potentially increase the federal budget deficit. Targeted debt forgiveness could stimulate specific sectors of the economy but might face challenges in equitable distribution. Tuition reform and increased funding for higher education represent a significant long-term investment but could lead to a more skilled and productive workforce and reduced inequality in access to higher education. Each policy option requires a thorough cost-benefit analysis to assess its overall impact on the economy and society.

Practical Implications for Students and Borrowers

The student loan interest deduction, while potentially beneficial, is significantly impacted by its limitations. Understanding these limitations is crucial for students and borrowers to accurately assess their tax liability and plan their repayment strategies effectively. The deduction’s impact varies greatly depending on income levels and the amount of interest paid.

The deduction’s limitation directly affects a student’s tax liability by reducing the amount of taxable income. This, in turn, lowers the overall tax owed. However, the phase-out limits mean that higher earners may not benefit as much or at all. The deduction is claimed as an “above-the-line” deduction, meaning it reduces your gross income before calculating your adjusted gross income (AGI). This makes it more valuable than itemized deductions, which are only beneficial if your total itemized deductions exceed the standard deduction.

Impact on Tax Liability

The student loan interest deduction reduces your taxable income dollar for dollar. For example, if a student paid $1,000 in student loan interest and is eligible for the full deduction, their taxable income is reduced by $1,000. This results in a lower tax bill, the exact amount depending on their tax bracket. However, if the same student’s modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds the phase-out limits, they may receive a reduced deduction or no deduction at all. For instance, a single filer with a MAGI exceeding $85,000 in 2023 would see their deduction reduced or eliminated completely.

Influence on Repayment Strategies

The availability and amount of the deduction can influence repayment strategies. Borrowers might consider accelerating payments to maximize the deduction in years with higher interest payments and lower income, before their MAGI rises above the phase-out thresholds. Conversely, those approaching the phase-out limits may strategically adjust their payments to remain eligible for the deduction. For example, a borrower anticipating a significant income increase might accelerate payments in the current year to benefit from a larger deduction before the income increase pushes them over the limit.

Claiming the Deduction

Claiming the student loan interest deduction involves several steps. First, gather all relevant documentation, including Form 1098-E, which shows the amount of student loan interest you paid. Next, complete the appropriate section on your tax return (Form 1040). Finally, review your return carefully before filing to ensure accuracy. Failure to accurately report the information could lead to delays or penalties.

Determining Eligibility

Determining eligibility for the student loan interest deduction requires a step-by-step process:

- Verify that you paid interest on a qualified student loan. This excludes loans used for purposes other than education.

- Check your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI). If your MAGI exceeds the phase-out limits for your filing status, your deduction may be reduced or eliminated.

- Confirm that you are legally obligated to repay the loan. This means the loan is in your name and you are currently making payments.

- Ensure you are not claimed as a dependent on someone else’s tax return. This is because dependent filers generally cannot claim this deduction.

- Gather Form 1098-E, which your lender should provide, detailing the interest you paid during the tax year. If you do not receive this form, contact your lender.

Last Point

Successfully navigating the complexities of the student loan interest deduction requires a thorough understanding of its limitations and eligibility criteria. While offering a valuable tax benefit for many, the deduction’s effectiveness varies significantly based on income and loan type. By carefully considering the information presented here, borrowers can make informed decisions about their repayment strategies and maximize their potential tax savings. Staying informed about potential legislative changes is equally important, as policy adjustments can significantly impact the future of this vital deduction.

Essential FAQs

What happens if my modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds the limit?

If your MAGI exceeds the limit, you may not be able to deduct any student loan interest, or your deduction may be reduced. The specific rules depend on the applicable tax year.

Can I deduct interest on private student loans?

Yes, you can deduct interest on both federal and private student loans, provided they meet all other eligibility requirements.

Do I need to itemize to claim the student loan interest deduction?

Yes, the student loan interest deduction is an itemized deduction. You cannot claim it if you use the standard deduction.

Where do I claim the student loan interest deduction on my tax return?

You claim it on Form 1040, Schedule A, Itemized Deductions.

What documents do I need to claim the deduction?

You’ll need Form 1098-E, Student Loan Interest Statement, which your lender provides. You will also need your tax return information.