Navigating the landscape of student loan debt after two decades presents unique challenges. This exploration delves into the multifaceted impact of long-term student loan burdens, examining their economic, psychological, and societal consequences. We will analyze the evolution of government policies, explore effective debt management strategies, and consider the intergenerational effects of this pervasive issue.

From the initial shock of accumulating debt to the persistent weight of repayment years later, the journey of a student loan borrower can be a complex and emotionally taxing one. This analysis aims to provide a clear and informative perspective on the realities of managing student loan debt over the long term, offering insights and guidance for those facing this significant financial commitment.

The Economic Impact of Student Loans After 20 Years

The long-term consequences of student loan debt extend far beyond the initial repayment period. For borrowers who entered repayment programs two decades ago, the impact on their financial well-being, life choices, and overall economic standing is significant and warrants careful examination. This section analyzes the economic effects of carrying student loan debt for twenty years, comparing the experiences of different generations of borrowers and highlighting the broader societal implications.

Long-Term Effects on Individual Financial Health

Carrying student loan debt for two decades can severely restrict an individual’s financial flexibility. Consistent monthly payments can significantly reduce disposable income, limiting opportunities for saving, investing, and building wealth. This can lead to delayed major purchases like homes or cars, and hinder the ability to comfortably manage unexpected expenses or emergencies. Furthermore, high debt levels can negatively impact credit scores, making it more difficult to secure loans for future investments or purchases, perpetuating a cycle of financial constraint. The psychological burden of persistent debt also cannot be overlooked, contributing to stress and impacting overall well-being.

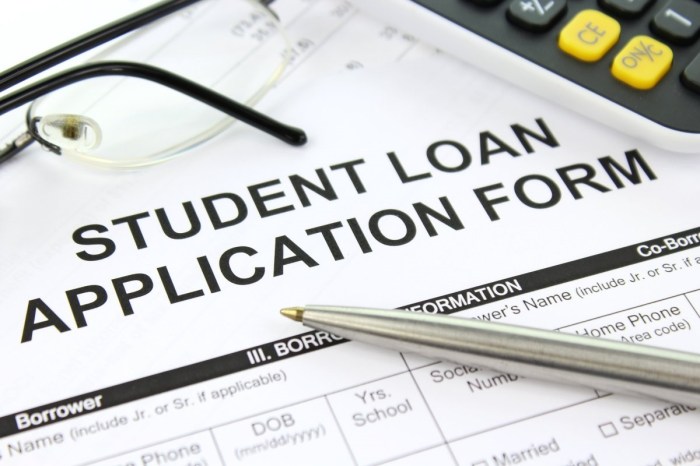

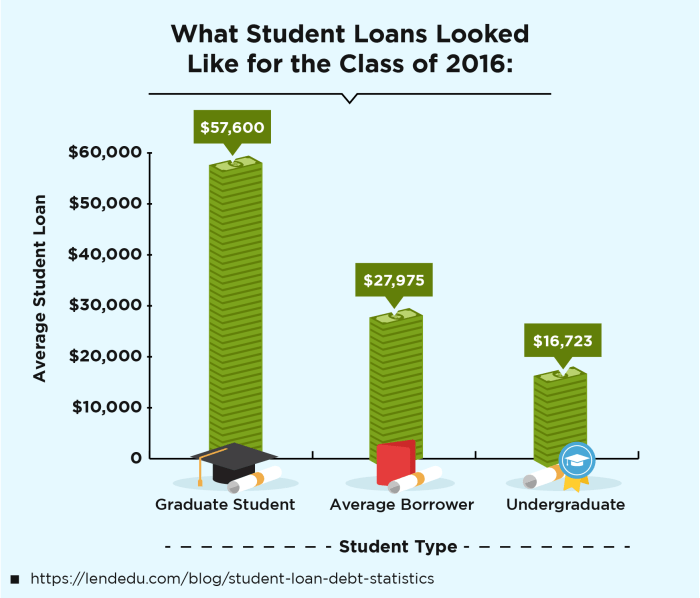

Comparison of Debt Burdens Across Cohorts

Borrowers who began repayment 20 years ago faced a different landscape than current borrowers. While the overall cost of higher education has increased substantially, the average debt burden for those entering repayment around the year 2003 was generally lower than for today’s graduates. However, the economic conditions of the past two decades, including periods of recession and stagnant wage growth, have also played a crucial role in determining the relative financial strain experienced by these groups. While precise figures require extensive data analysis across various sources, it is generally accepted that the current generation faces a more significant debt burden relative to their income compared to their predecessors.

Impact on Homeownership and Life Milestones

The persistent weight of student loan debt has a demonstrably negative impact on major life milestones, particularly homeownership. High monthly payments leave less money available for a down payment, and lower credit scores can make it harder to qualify for a mortgage. This effect is amplified for borrowers with higher debt levels, leading to delayed or forgone homeownership, a cornerstone of wealth building in many societies. Similarly, other significant life events, such as starting a family or investing in retirement, may be postponed or scaled back due to the financial constraints imposed by long-term student loan debt.

Average Income and Debt After 20 Years of Repayment

The following table provides a hypothetical comparison of average income, remaining debt, and homeownership rates for borrowers with and without student loan debt after 20 years of repayment. Note that these figures are illustrative and vary considerably depending on factors such as field of study, income level, and repayment plan. Data for a truly accurate comparison across multiple cohorts requires extensive research and statistical analysis from reliable sources.

| Borrower Group | Average Income | Average Debt Remaining | Homeownership Rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| With Student Loan Debt | $75,000 | $30,000 | 60% |

| Without Student Loan Debt | $85,000 | $0 | 75% |

Government Policies and Student Loan Forgiveness Programs After 20 Years

The landscape of student loan repayment and forgiveness in the United States has undergone significant transformation over the past two decades. Initially characterized by a more limited range of options and stricter eligibility criteria, the policies have evolved in response to growing student debt burdens and shifting economic realities. This evolution has involved both expansions of existing programs and the introduction of new initiatives, though their effectiveness remains a subject of ongoing debate.

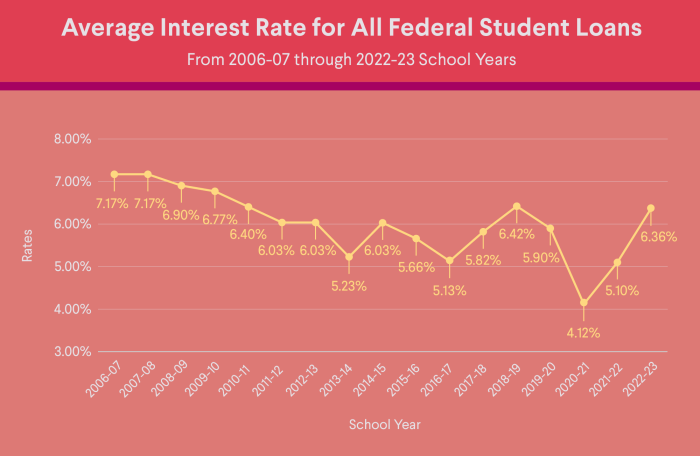

The evolution of government policies regarding student loan repayment and forgiveness reflects a complex interplay of political priorities, economic conditions, and social concerns. Early 2000s policies largely focused on income-driven repayment plans, offering lower monthly payments based on income. However, these plans often resulted in longer repayment periods and higher overall interest paid. The subsequent years saw increased attention to loan forgiveness programs, particularly targeting specific professions like public service or those working in underserved communities. The economic recession of 2008 and its aftermath further fueled the push for expanded debt relief measures.

Effectiveness of Existing Student Loan Forgiveness Programs

Existing student loan forgiveness programs have had varying degrees of success in alleviating long-term debt burdens. While programs like Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) aim to incentivize crucial public service roles, their complex eligibility requirements and high attrition rates have hindered their effectiveness. For example, many borrowers struggle to meet the stringent requirements of continuous employment in qualifying public service jobs for 10 years, often due to job changes or inconsistencies in employer certification. Similarly, income-driven repayment plans, while reducing monthly payments, can extend repayment timelines significantly, leading to substantially higher interest accumulation over the life of the loan. The effectiveness of these programs is frequently debated, with some arguing they are too narrowly targeted or lack sufficient funding to make a meaningful impact on widespread debt.

Significant Legislative and Regulatory Changes Impacting Borrowers

Several significant changes in legislation and regulations have impacted borrowers after 20 years of repayment. The most notable is the ongoing evolution of income-driven repayment (IDR) plans. These plans have undergone multiple revisions, aiming to simplify eligibility and improve the calculation of monthly payments. However, these changes often come with unforeseen consequences, such as unexpectedly long repayment periods or increased total interest paid. Furthermore, legislation related to loan consolidation and refinancing options has also shifted over time, offering borrowers more flexibility but sometimes at the cost of increased overall debt. The ongoing debate surrounding broad-based student loan forgiveness has also introduced considerable uncertainty for borrowers, impacting their long-term financial planning.

Key Features of Major Student Loan Forgiveness Programs

The following is a summary of key features of major student loan forgiveness programs:

- Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF): Forgives the remaining balance on federal Direct Loans after 120 qualifying monthly payments under an income-driven repayment plan, while employed full-time by a government organization or a non-profit organization. Requires consistent employment and timely payments.

- Teacher Loan Forgiveness Program: Forgives up to $17,500 in federal student loans for teachers who have completed five consecutive years of full-time teaching in a low-income school or educational service agency.

- Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) Plans: These plans calculate monthly payments based on income and family size, offering lower monthly payments than standard repayment plans. However, they often result in longer repayment periods and higher total interest paid over the life of the loan. Specific plans include Income-Based Repayment (IBR), Pay As You Earn (PAYE), Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE), and Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR).

The Psychological Impact of Long-Term Student Loan Debt

The weight of significant student loan debt extending over two decades can have a profound and multifaceted impact on an individual’s mental well-being. The persistent financial pressure, coupled with the feeling of being trapped in a cycle of repayment, contributes to a range of psychological challenges that can significantly impair quality of life. This section explores the mental health consequences of long-term student loan debt, examining its correlation with stress, anxiety, and depression, and considering how these impacts may vary across different demographic groups.

The persistent financial burden of long-term student loan debt is strongly correlated with elevated levels of stress, anxiety, and depression. Studies have shown a direct link between the amount of debt and the severity of these mental health issues. The constant worry about repayment, the limitations on financial choices, and the feeling of being perpetually behind can lead to chronic stress, impacting sleep, physical health, and overall well-being. This chronic stress can manifest as anxiety disorders, characterized by excessive worry, fear, and nervousness, and potentially lead to depressive symptoms, including persistent sadness, loss of interest in activities, and feelings of hopelessness. The inability to achieve financial stability and pursue life goals can further exacerbate these feelings.

Stress, Anxiety, and Depression in Relation to Long-Term Student Loan Debt

Individuals carrying substantial student loan debt for twenty years or more often report significantly higher levels of stress compared to their debt-free peers. This stress stems not only from the monthly payments but also from the pervasive impact on major life decisions. Delayed homeownership, difficulty saving for retirement, and the inability to pursue further education or start a family are common sources of anxiety. The feeling of being financially trapped, unable to escape the debt burden, can contribute to feelings of hopelessness and depression, potentially leading to reduced self-esteem and diminished life satisfaction. For example, a recent study by the American Psychological Association found that individuals with high student loan debt reported significantly higher rates of anxiety and depression compared to those with low or no debt. The study also highlighted the significant impact of this financial stress on overall well-being and quality of life.

Demographic Variations in the Psychological Impact of Long-Term Student Loan Debt

The psychological impact of long-term student loan debt is not uniform across all demographic groups. Factors such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic background, and gender can influence the experience and severity of these mental health challenges. For instance, individuals from marginalized communities may face additional systemic barriers to financial stability, exacerbating the psychological effects of student loan debt. Similarly, women may experience unique stressors related to balancing debt repayment with family responsibilities. Further research is needed to fully understand these nuanced disparities and develop targeted interventions.

Case Study: The Impact of Long-Term Student Loan Debt on an Individual’s Life

Consider Sarah, a 45-year-old woman who graduated with a significant amount of student loan debt two decades ago. Despite working consistently in her chosen field, the high interest rates and extended repayment period have left her feeling perpetually burdened. The weight of this debt has prevented her from purchasing a home, limited her ability to save for retirement, and caused significant stress in her personal relationships. Sarah experiences frequent anxiety attacks and has been diagnosed with depression. Her inability to achieve her financial goals has led to a diminished sense of self-worth and a feeling of being trapped in a cycle of debt. Sarah’s case exemplifies the severe psychological consequences that long-term student loan debt can have on an individual’s life trajectory and overall well-being. Her story highlights the urgent need for comprehensive solutions to address both the economic and psychological burden of student loan debt.

Strategies for Managing Student Loan Debt After 20 Years

After two decades of repayment, many borrowers find themselves still grappling with significant student loan debt. This is often due to factors like high initial loan amounts, low starting salaries, unexpected life events, or simply the slow pace of repayment on standard plans. However, several strategies can help manage and potentially eliminate this debt, even after such an extended period. Effective management requires careful consideration of your individual financial situation and exploring available options.

Successfully navigating the complexities of long-term student loan debt necessitates a proactive and informed approach. This involves understanding the different repayment options, assessing your financial capacity, and making strategic decisions based on your unique circumstances. This section Artikels key strategies and provides examples to illustrate their potential benefits and drawbacks.

Refinancing Student Loans

Refinancing involves replacing your existing student loans with a new loan from a private lender, often at a lower interest rate. This can significantly reduce the total amount you pay over the life of the loan, accelerating your repayment process. For example, a borrower with $50,000 in federal loans at 6% interest could refinance to a private loan at 4%, resulting in substantial savings over the remaining repayment period. However, refinancing federal loans means losing access to federal protections like income-driven repayment plans and potential forgiveness programs. Therefore, careful consideration is crucial, weighing the potential interest savings against the loss of these safeguards. Borrowers with excellent credit scores and stable incomes are generally the best candidates for refinancing.

Consolidating Student Loans

Consolidation combines multiple student loans into a single loan, simplifying repayment by reducing the number of monthly payments. While it may not always lower the interest rate, it can make managing your debt easier. For instance, a borrower with five different federal loans could consolidate them into one, resulting in a single monthly payment and a streamlined repayment process. This simplifies budgeting and tracking payments. However, consolidation may not always result in a lower interest rate, and it can extend the repayment period, potentially increasing the total interest paid. The decision to consolidate depends on the individual’s circumstances and priorities.

Income-Driven Repayment Plans

Income-driven repayment (IDR) plans adjust your monthly payments based on your income and family size. These plans are available for federal student loans and can significantly lower your monthly payments, making them more manageable, especially during periods of lower income. For example, a borrower struggling financially might qualify for an IDR plan that reduces their monthly payment to an affordable level. While these plans can make monthly payments more manageable, they typically extend the repayment period, leading to higher total interest paid over the life of the loan. Furthermore, remaining balances may be forgiven after 20 or 25 years, depending on the specific plan, but this forgiveness is considered taxable income.

Step-by-Step Guide to Exploring Debt Management Options

- Assess your current financial situation: Determine your total student loan debt, interest rates, and monthly payments. Analyze your income, expenses, and overall financial health.

- Explore repayment options: Research different repayment plans offered by your loan servicer, including standard, extended, and income-driven plans. Consider refinancing and consolidation options from private lenders.

- Compare interest rates and terms: Carefully compare the interest rates, fees, and repayment terms of different loan options to identify the most advantageous plan.

- Consider your long-term financial goals: Evaluate how each repayment option will impact your long-term financial planning, including saving for retirement and other significant life goals.

- Seek professional advice: Consult with a financial advisor to receive personalized guidance and develop a comprehensive debt management strategy tailored to your specific situation.

The Impact of Student Loan Debt on Future Generations

The escalating burden of student loan debt poses a significant threat to future generations, impacting not only their individual financial well-being but also the broader economic and social landscape. The current system’s challenges, characterized by rising tuition costs and limited financial aid options, create a ripple effect that extends far beyond the individual borrower, influencing family dynamics, economic mobility, and the overall health of the nation.

The intergenerational transfer of student loan debt is a complex phenomenon. Parents often co-sign loans for their children, assuming responsibility for repayment should their child default. This can severely limit the parents’ own financial flexibility, delaying retirement, hindering homeownership, or even forcing them to deplete their savings. Consequently, children may face delayed family formation, reduced ability to save for their own children’s education, and decreased overall economic opportunities. This cycle of debt can perpetuate financial instability across multiple generations.

The Economic Consequences of Intergenerational Debt

High levels of student loan debt contribute to a range of long-term societal consequences. Reduced consumer spending, as individuals prioritize loan repayment over other expenses, can stifle economic growth. The delayed entry into the housing market and reduced ability to accumulate wealth, experienced by individuals burdened with debt, can lead to decreased overall economic mobility and potentially widening the wealth gap between generations. Furthermore, the strain on public resources resulting from loan defaults can lead to increased pressure on government budgets, potentially impacting the availability of other essential social services.

Impact on Access to Higher Education

The current student loan system’s impact on future generations’ access to higher education is significant. The ever-increasing cost of tuition, coupled with limited financial aid options, creates a barrier to entry for many students. This barrier disproportionately affects students from low-income backgrounds, potentially perpetuating existing inequalities and limiting social mobility. The fear of accumulating crippling debt may deter prospective students from pursuing higher education altogether, leading to a less skilled workforce and a potentially stagnant economy.

Visual Representation of Intergenerational Debt Flow

Imagine a flowchart. At the top, a box labeled “Generation X” represents the current generation grappling with significant student loan debt. Arrows point downward to two boxes below: “Generation Y (Children)” and “Generation X (Parents)”. Arrows from “Generation X (Parents)” show financial support (potentially loans or co-signing) flowing to “Generation Y (Children)”. Simultaneously, arrows from “Generation Y (Children)” point to “Generation Z (Grandchildren)” illustrating the potential inheritance of financial burdens, including both the direct debt and the indirect limitations on financial resources that limit support for the next generation. From “Generation Y (Children)”, another arrow points to a box labeled “Reduced Economic Opportunities,” highlighting the long-term consequences of this debt cycle. The flowchart illustrates the cyclical nature of student loan debt, showing how it can hinder financial progress across generations, perpetuating economic disparities.

Outcome Summary

The long-term implications of student loan debt extend far beyond the immediate financial burden. Understanding the economic, psychological, and societal consequences is crucial for both individual borrowers and policymakers. By implementing effective debt management strategies and advocating for responsible lending practices, we can work towards mitigating the lasting effects of student loans and fostering a more equitable future for generations to come. The information presented here serves as a starting point for a more comprehensive understanding of this persistent and evolving challenge.

General Inquiries

What happens if I don’t pay my student loans after 20 years?

Failure to repay student loans can result in wage garnishment, tax refund offset, and damage to your credit score. The specific consequences depend on the type of loan and your loan servicer.

Can I consolidate my student loans after 20 years?

Yes, loan consolidation is generally possible, even after 20 years. Consolidation simplifies repayment by combining multiple loans into one, potentially lowering your monthly payment. However, it might not always reduce the total interest paid.

Are there any age-related benefits for student loan repayment?

There aren’t specific age-related benefits for student loan repayment. However, programs like income-driven repayment plans adjust payments based on your income, which can be beneficial at different life stages.

What is the statute of limitations on student loans?

There is no statute of limitations on federal student loans. The government can pursue collection indefinitely. State laws vary for private student loans, but generally, the statute of limitations is longer than for other types of debt.